It’s hard to believe that the month of October is coming to a close. After that, I’ll only have one week left working at the Bighorn National Forest and I’ll have to say goodbye to the place where I’ve spent 5 months learning the forests and meadows that make up the mountain range, 5 months scouting, collecting, and shipping seed off to be used for restoration efforts.

Uncharacteristically hot and dry fall weather (we were breaking high temperature records almost every day out here throughout September), resulted in perfect conditions for a fire, and a lightning strike in the deep woods meant just that. The Elk Fire, which started September 27, grew to about 97,000 acres (both on and off the forest) in the approximate month it was actively burning. As of writing this in late October it’s not 100% contained, but some much-needed precipitation and cooler weather have bolstered the tireless efforts of firefighters and other Forest Service employees, meaning that the threat of the fire spreading is down to almost zero.

It’s one thing to hear about fires across the country, and another to directly see the impact: a bustling office, evacuation orders in nearby towns, and heavy smoke throughout the area. We spent the entire summer getting to know that mountain, and now a good portion of it was burning. In fact, some of the areas impacted by the fire were places we collected seed – I didn’t imagine that I’d get to see an event that would require hands on restoration work the same summer I was collecting seed for said restoration!

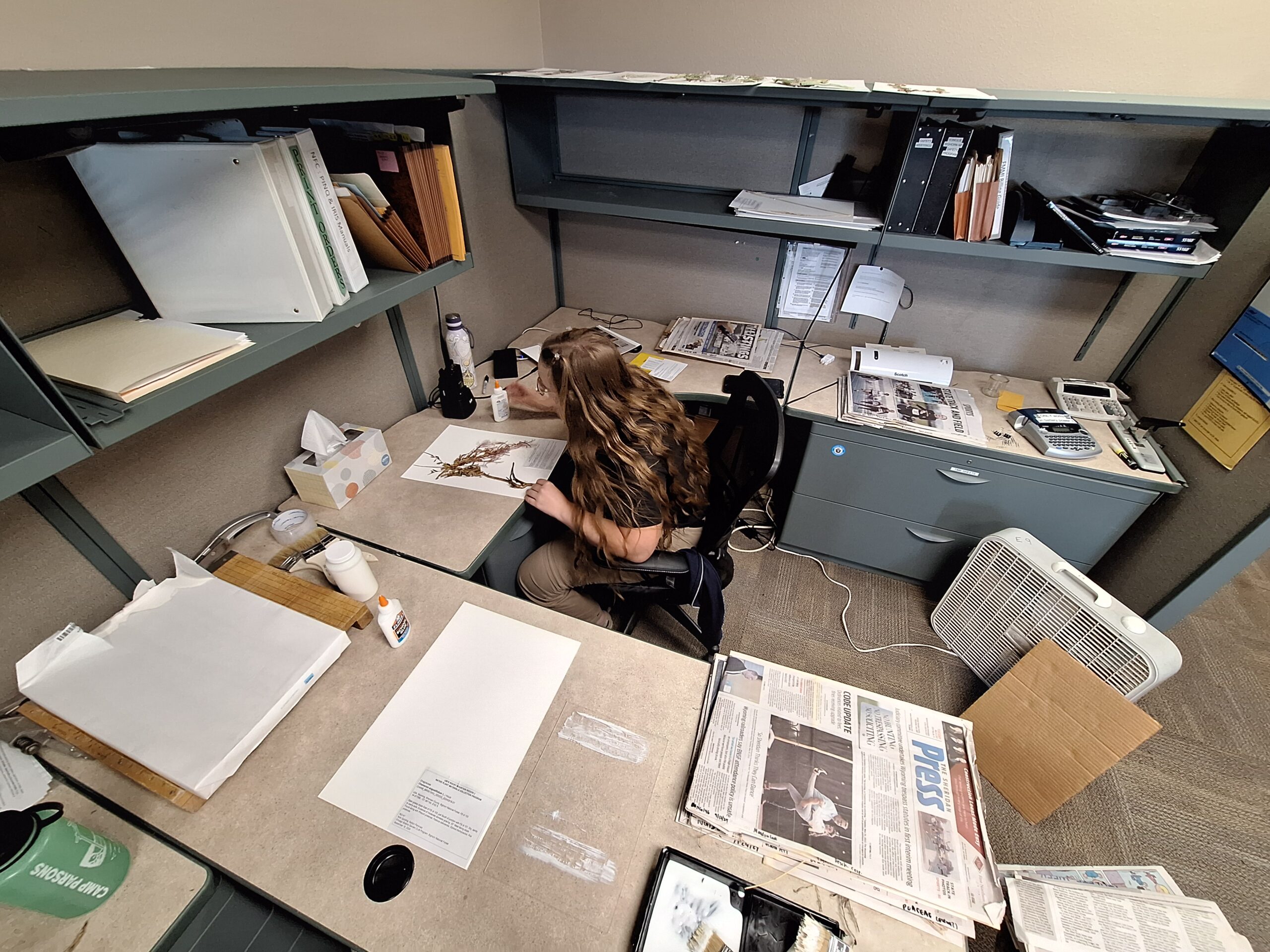

Because my co-intern, Nick, and I are not actually Forest Service Employees, we were not allowed to do anything fire related (including driving people and supplies around), and vehicles were in high demand. So, October was mostly a month of days spent in the office.

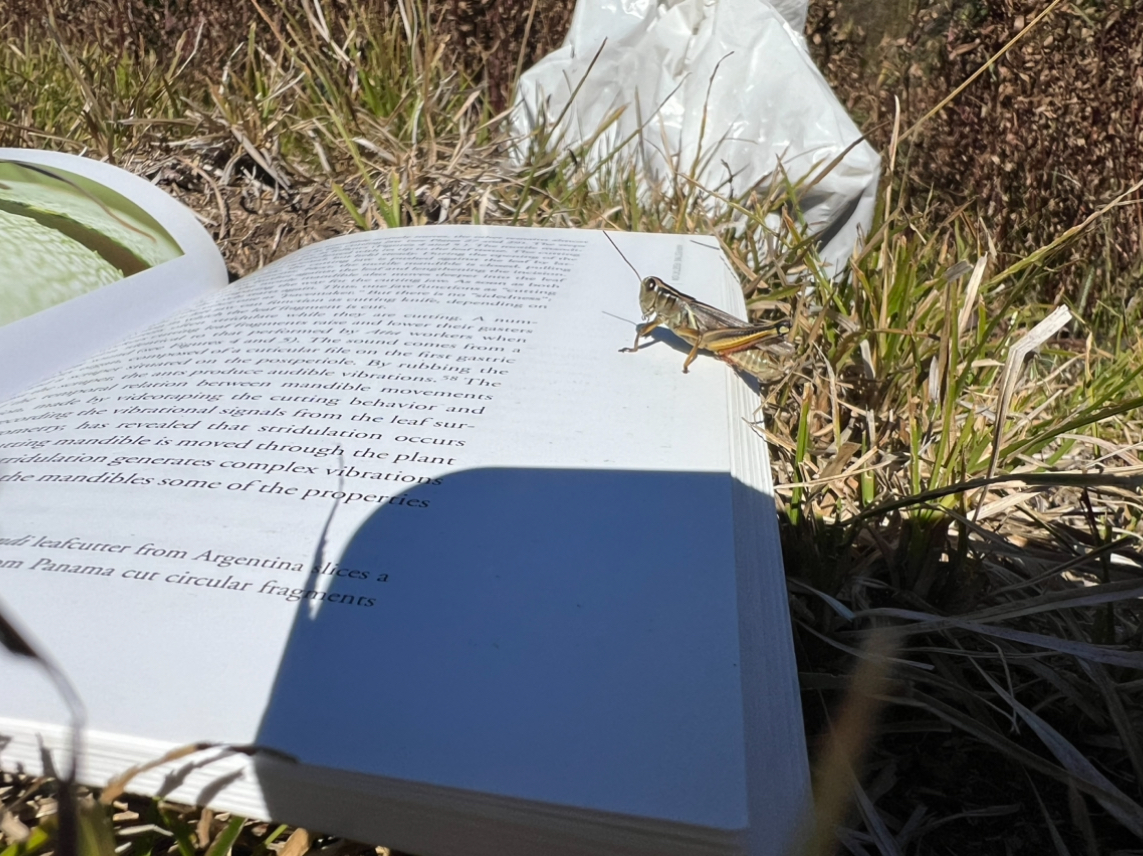

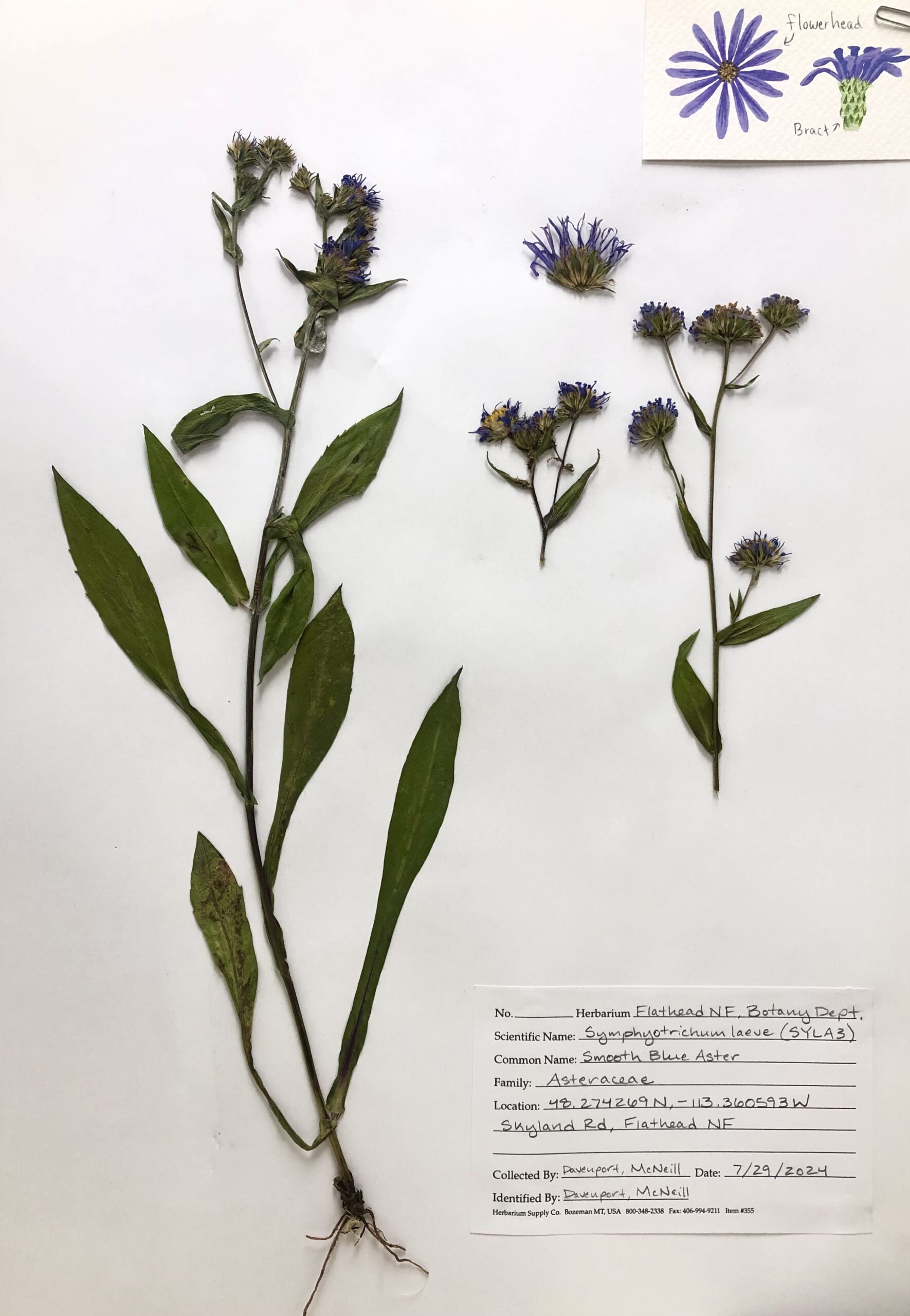

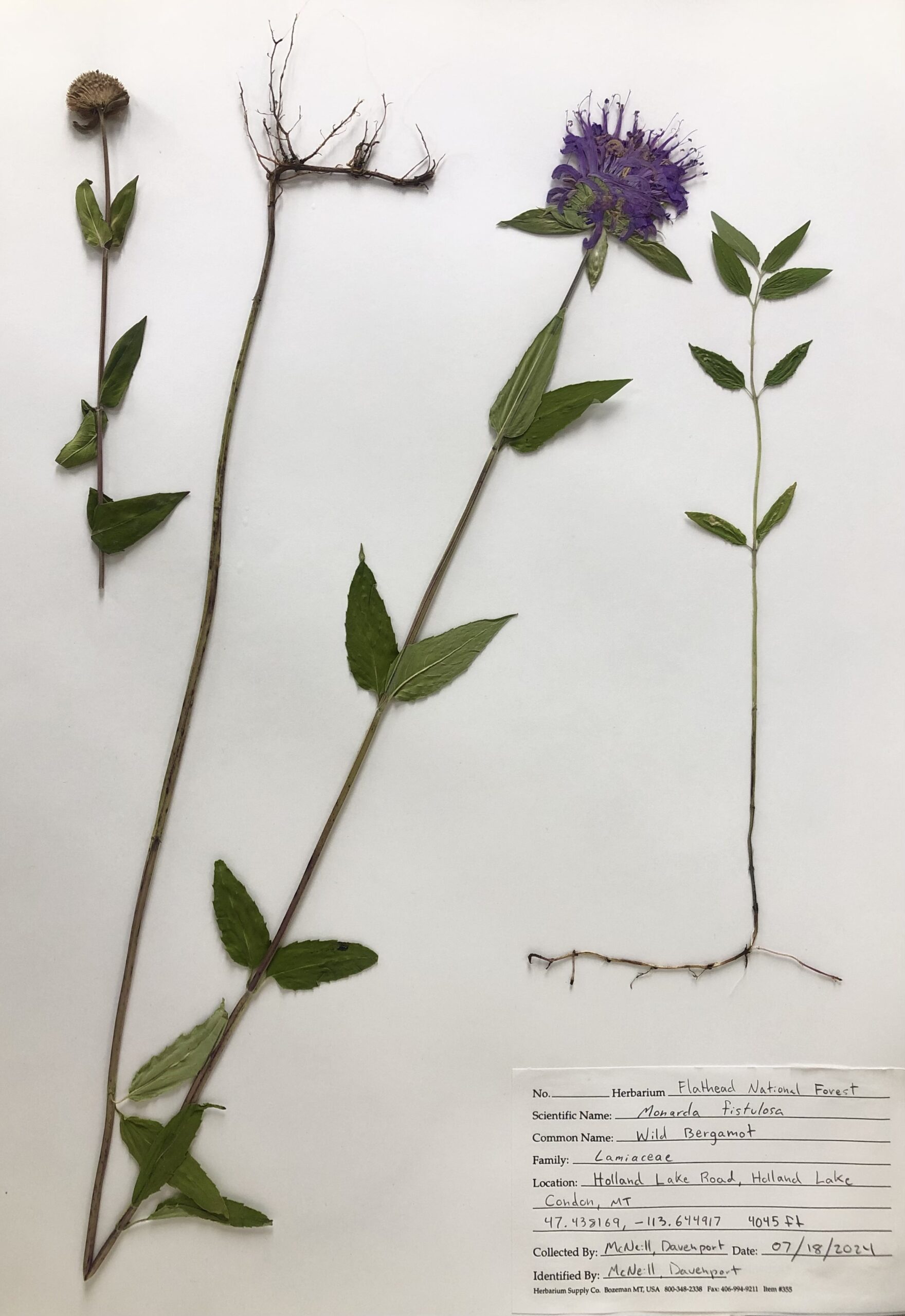

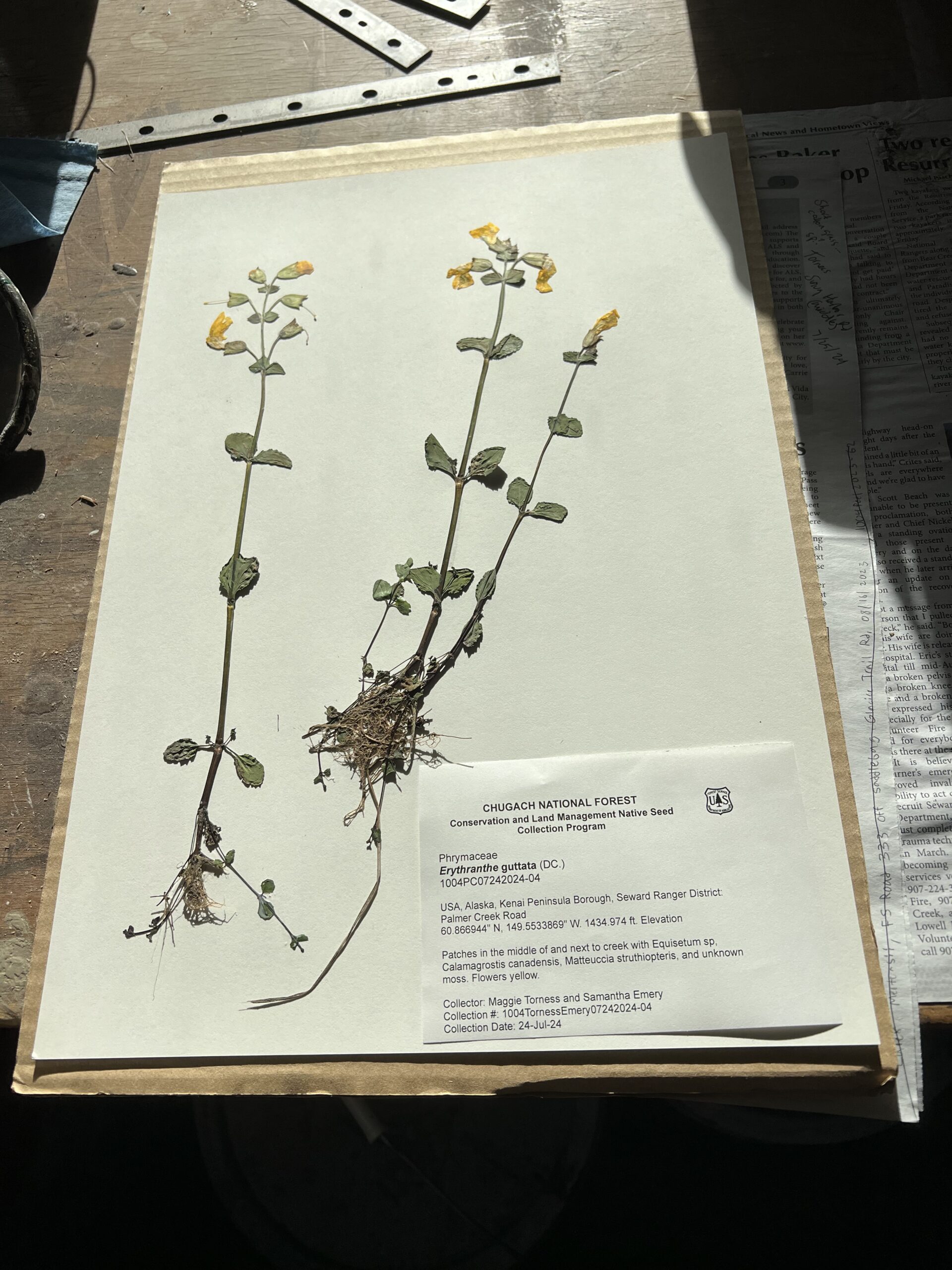

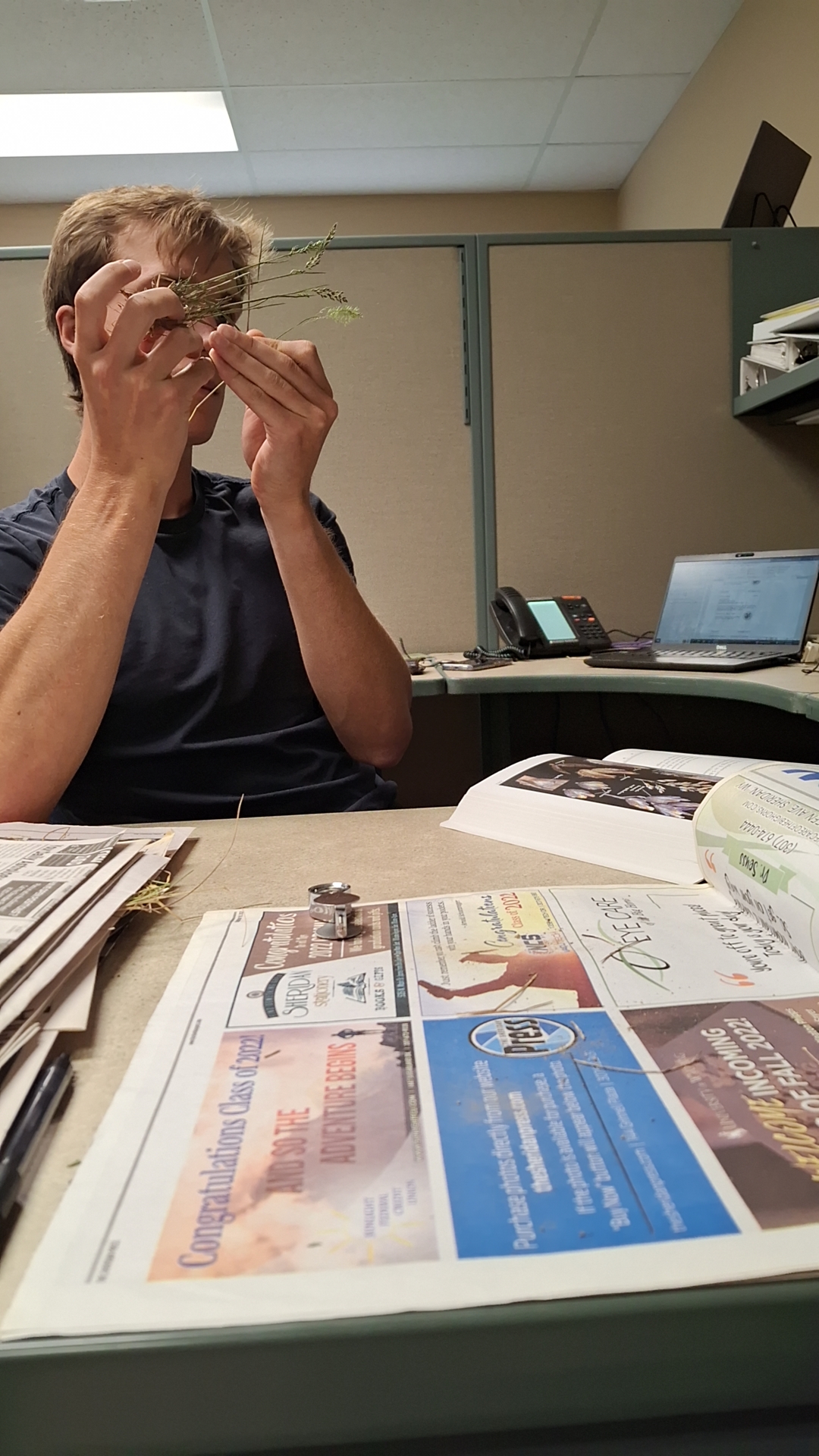

Since late August and all of September were peak seed collection times, we were left with a backlog of plants to both identify and mount. This involved many hours making our way through dichotomous keys, either quickly coming to a conclusion about the species in front of us or lamenting about how difficult an ID ended up being, finding ourselves asking questions like: why are all the wheatgrasses so similar, and why do they span multiple genera? How do you actually tell if something is rhizomatous or not? What does the author even mean by this – you can’t convince me that there isn’t a more objective way to describe something than “relatively long”? And what even is a keel, really? (shoutout to the “Plant Identification Terminology” book, the real MVP of the month). At some point the hyper-specific language of dichotomous keys really starts to get to you. For example, after a couple hours of keying out some grasses, Nick described a plant pointing upwards (as opposed to creeping along a surface) as: “pointing in the direction opposite to the ground,” and I don’t think there’s a way to sound more like Dorn (the author of the Wyoming flora).

In particular, the genus Erigeron, which we (unfortunately) collected lots of in an effort to find one of our target species Erigeron speciosus, gave us lots of trouble; our specimen vs. the images of the species we ended on at the end of the key never quite seemed to match (I don’t know if I can call an image search another MVP because too often they just contradicted our key based identifications, but know that it was utilized often), so our IDs were questionable at best. You know you’ve spent too much time with one genus when you have the beginning couplets memorized.

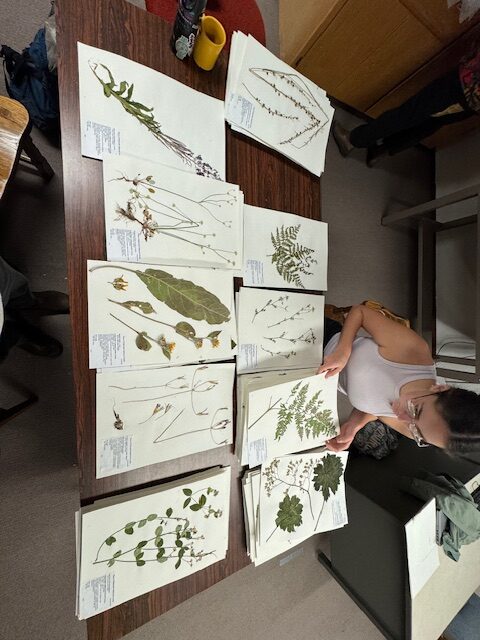

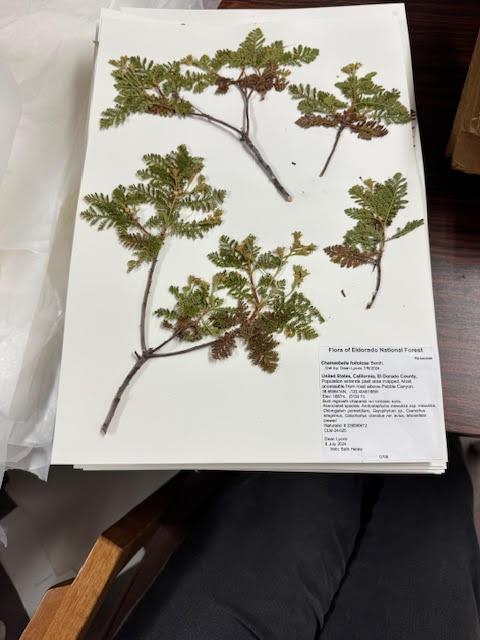

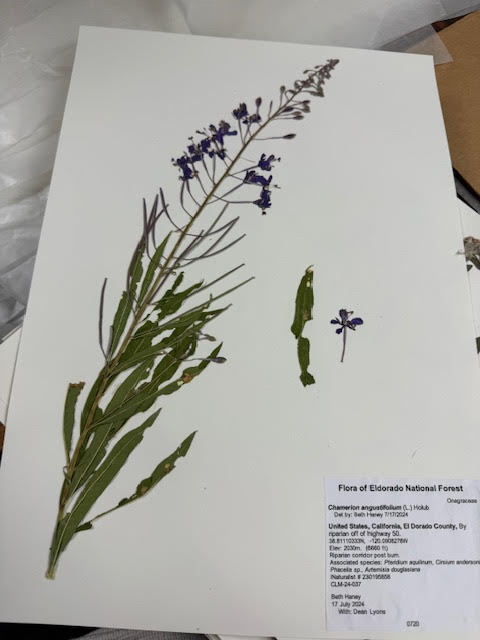

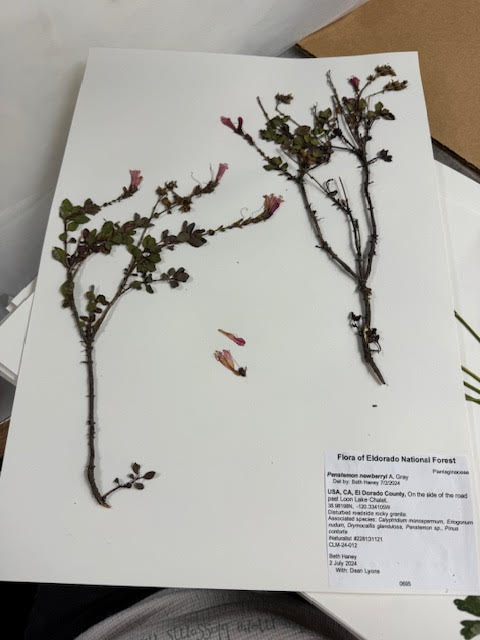

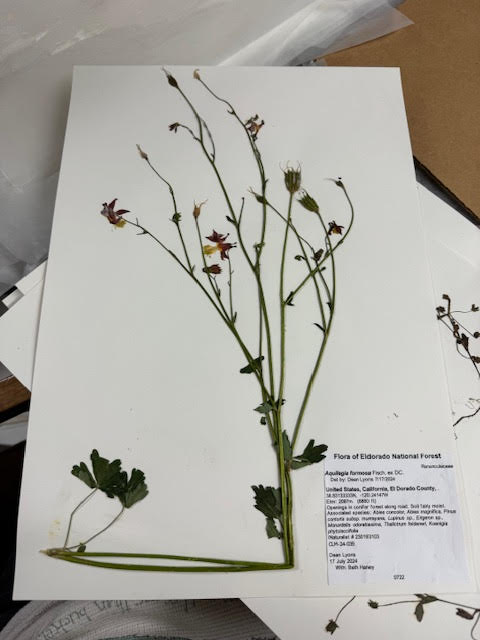

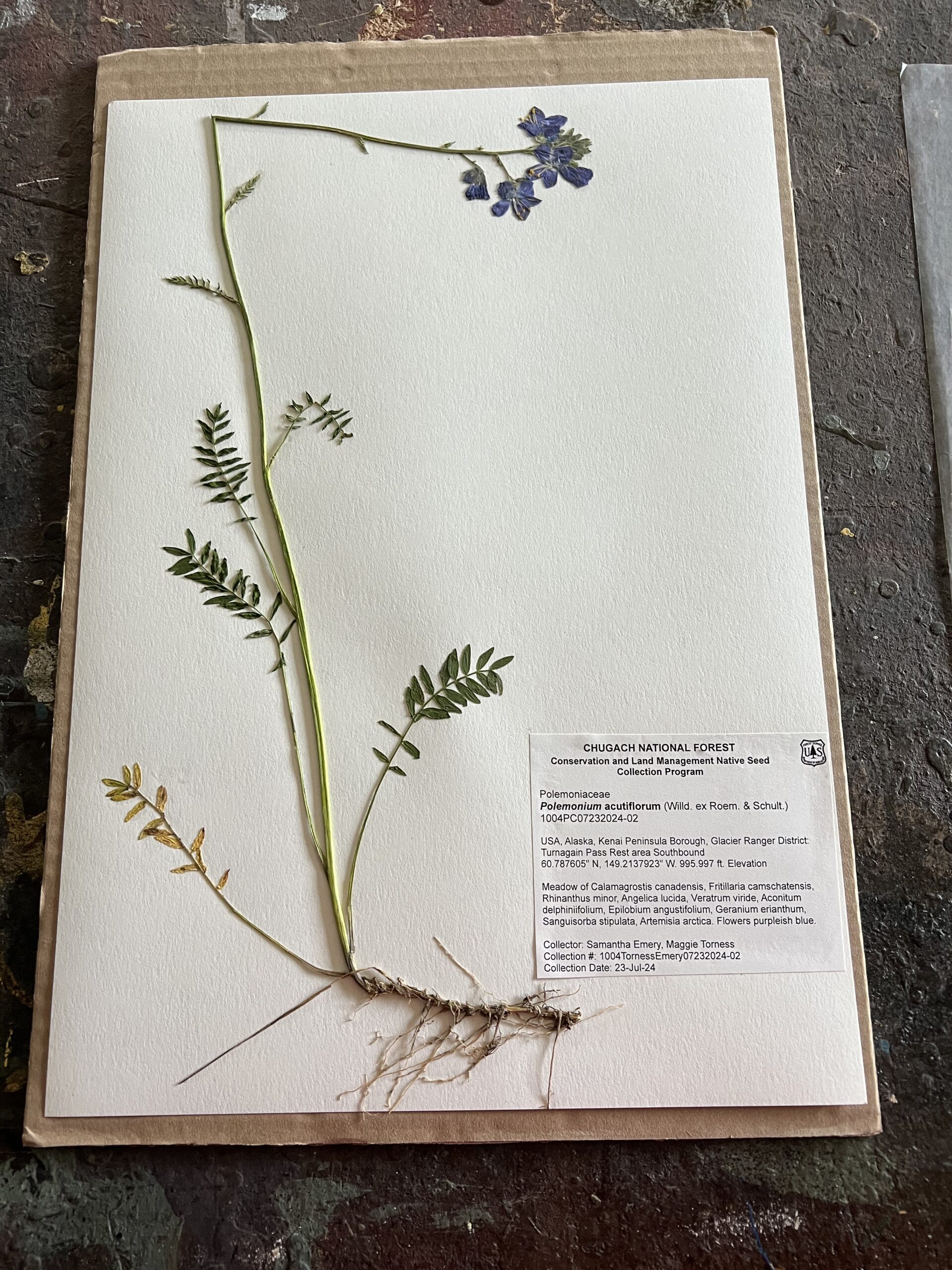

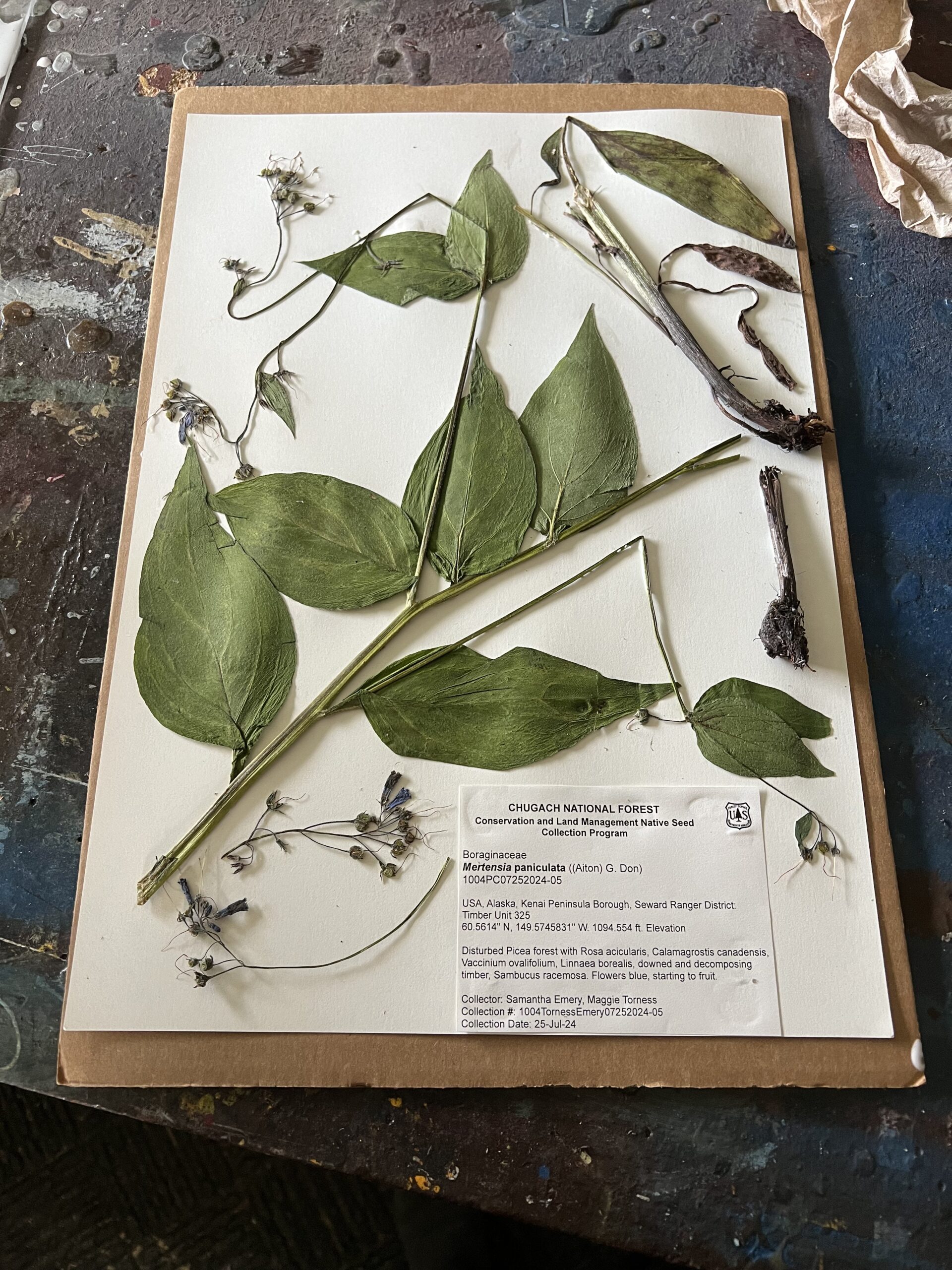

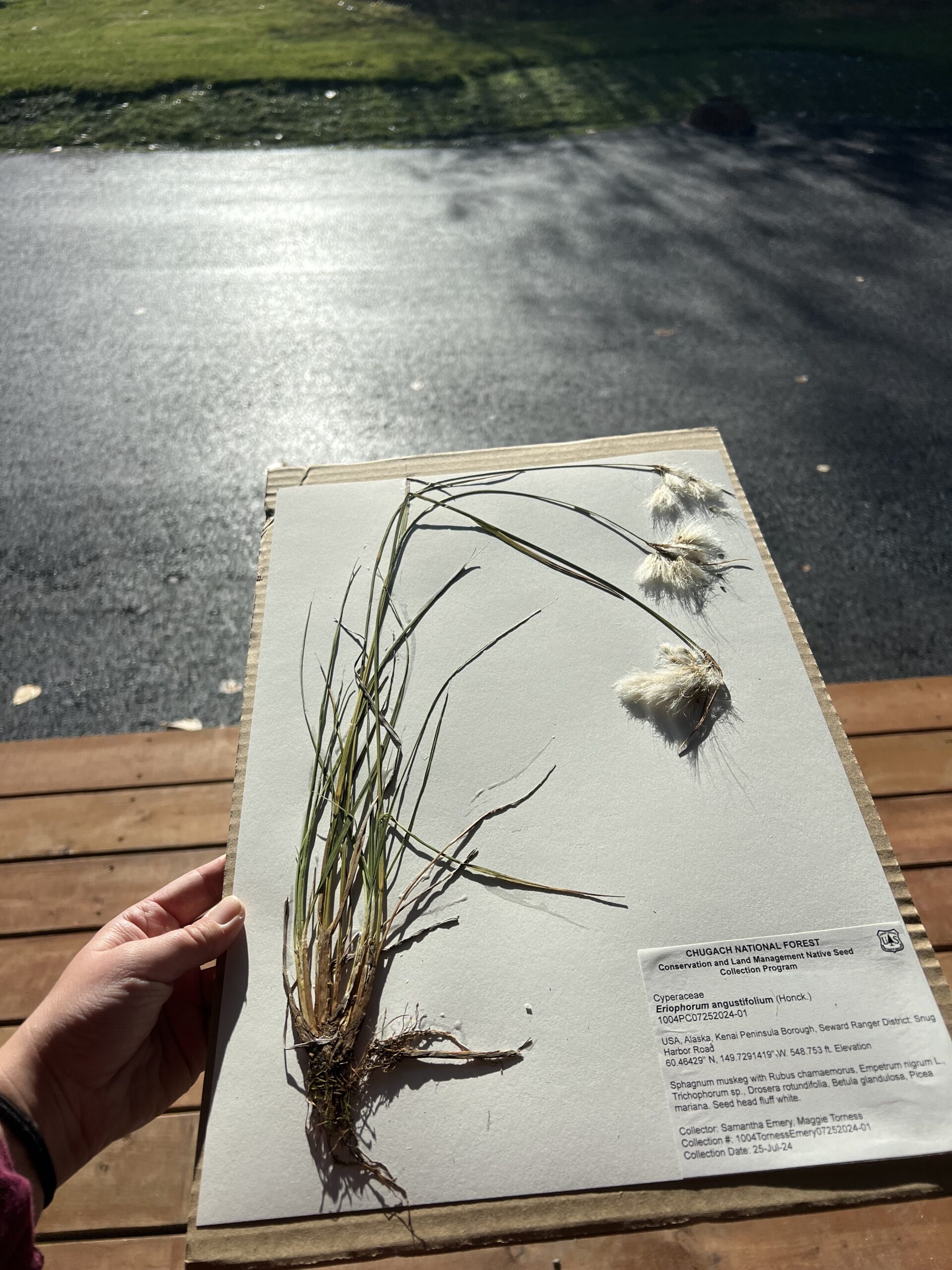

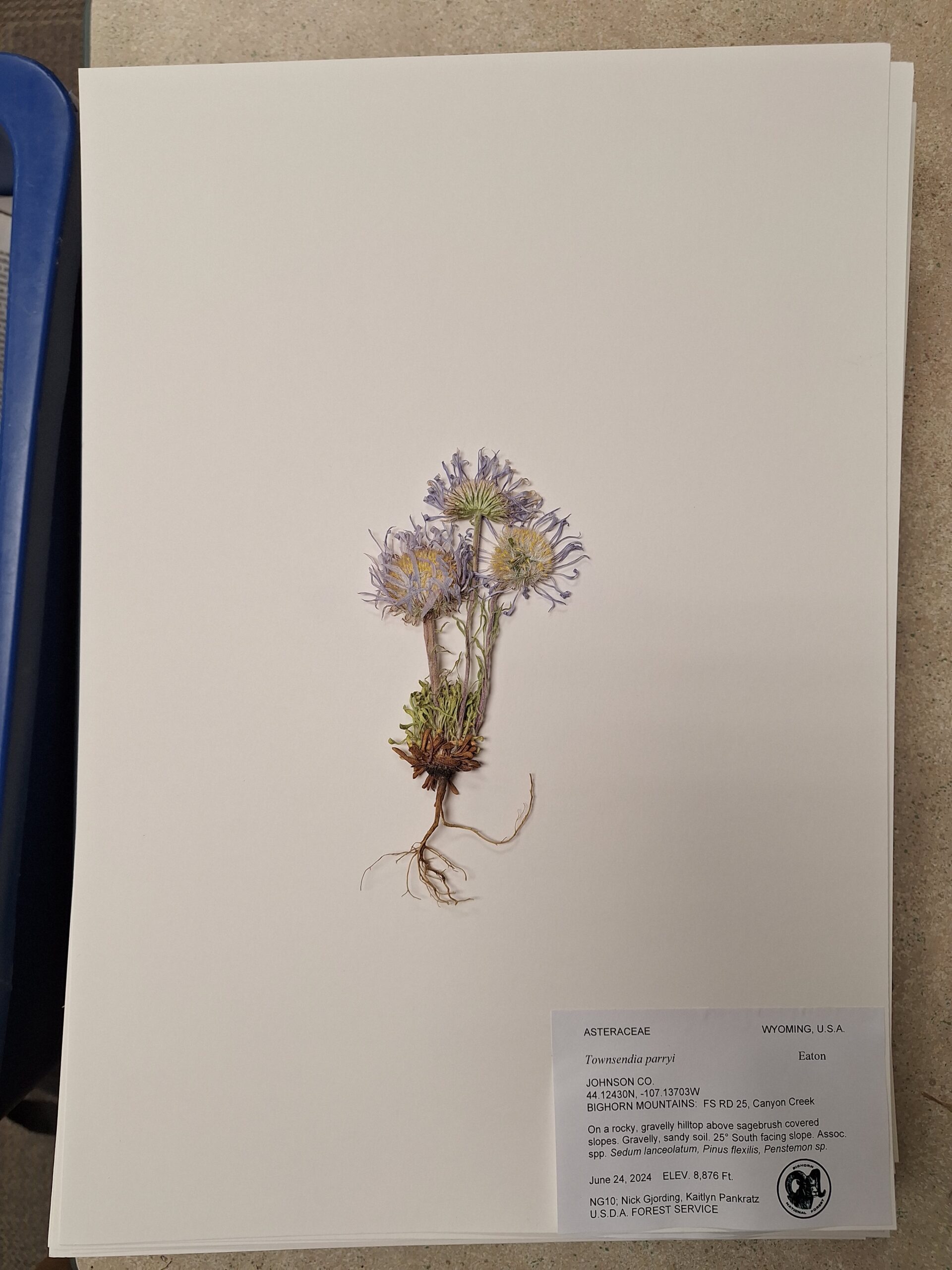

After ID came easily one of my favorite parts of the month: getting to mount all of the plants we collected onto herbarium sheets (which with the two vouchers for each population we collected seed from and all the other plants we grabbed, ended up being about 200). It was basically a big arts and crafts project, which, as a crafting girlie at heart, was right up my alley. I honestly would have been satisfied if all we had done this month was mount specimen.

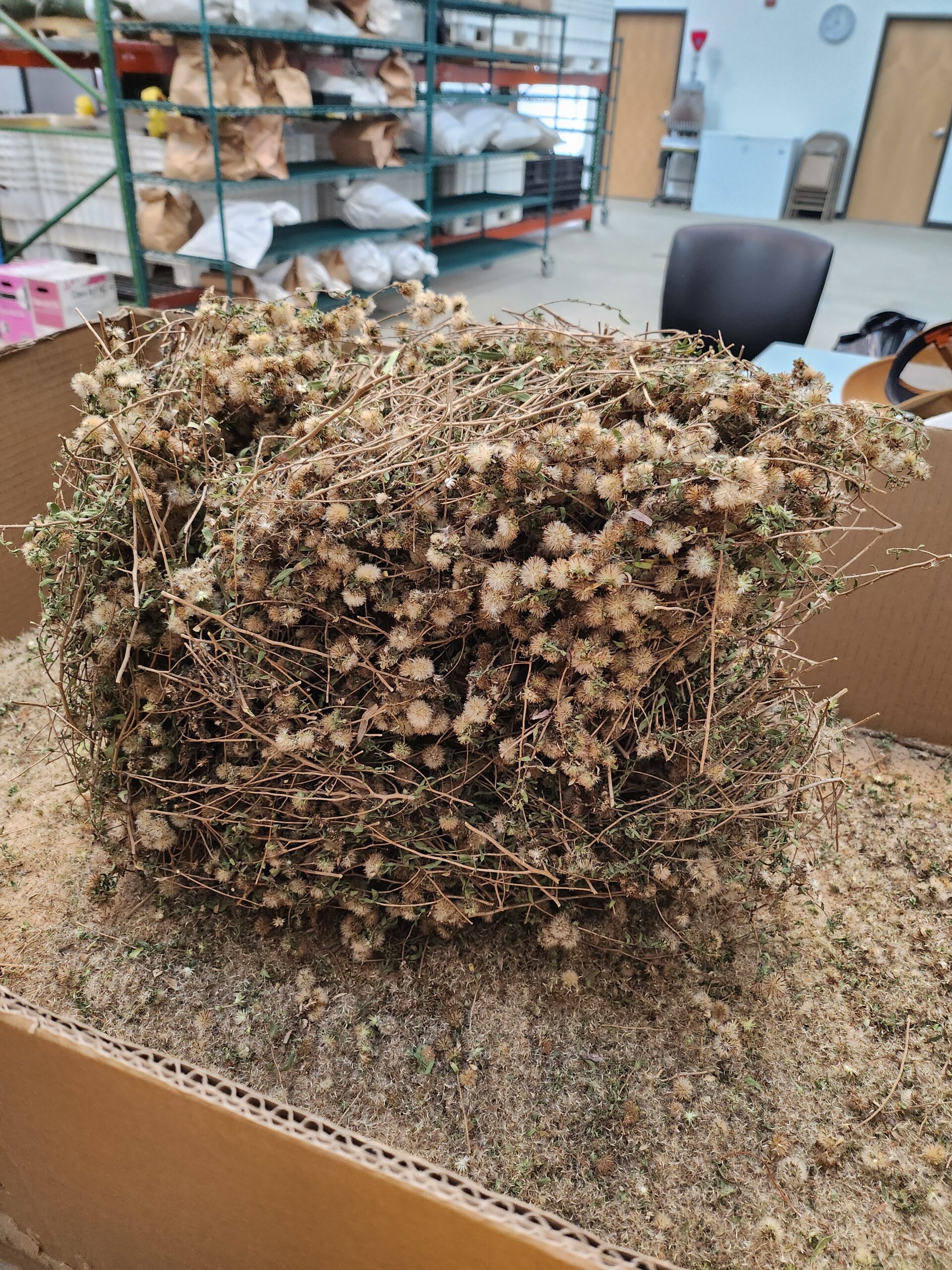

Don’t let all of the office time fool you, though; we still had the opportunity to get out on the mountain and collect some seed this month. A big thank you to Artemisia tridentata (sagebrush) for having mature seed so late in the season. It was a great collection to finish the season on – there are some pretty large populations of it on the forest so we got to collect a lot of seed from just the two collections we did, and it’s a crucial part of our forest’s ecosystem stability.

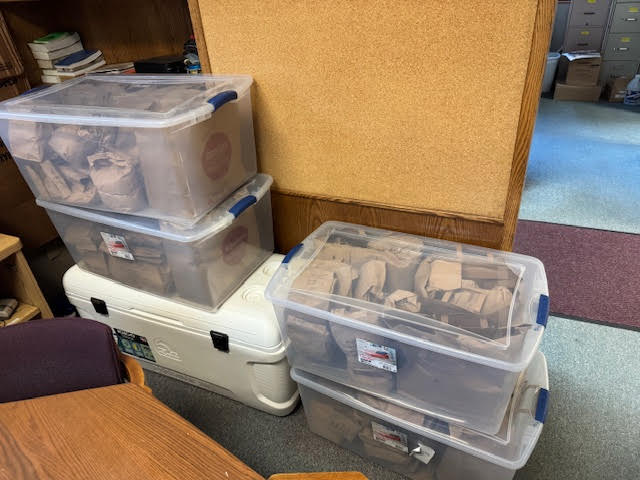

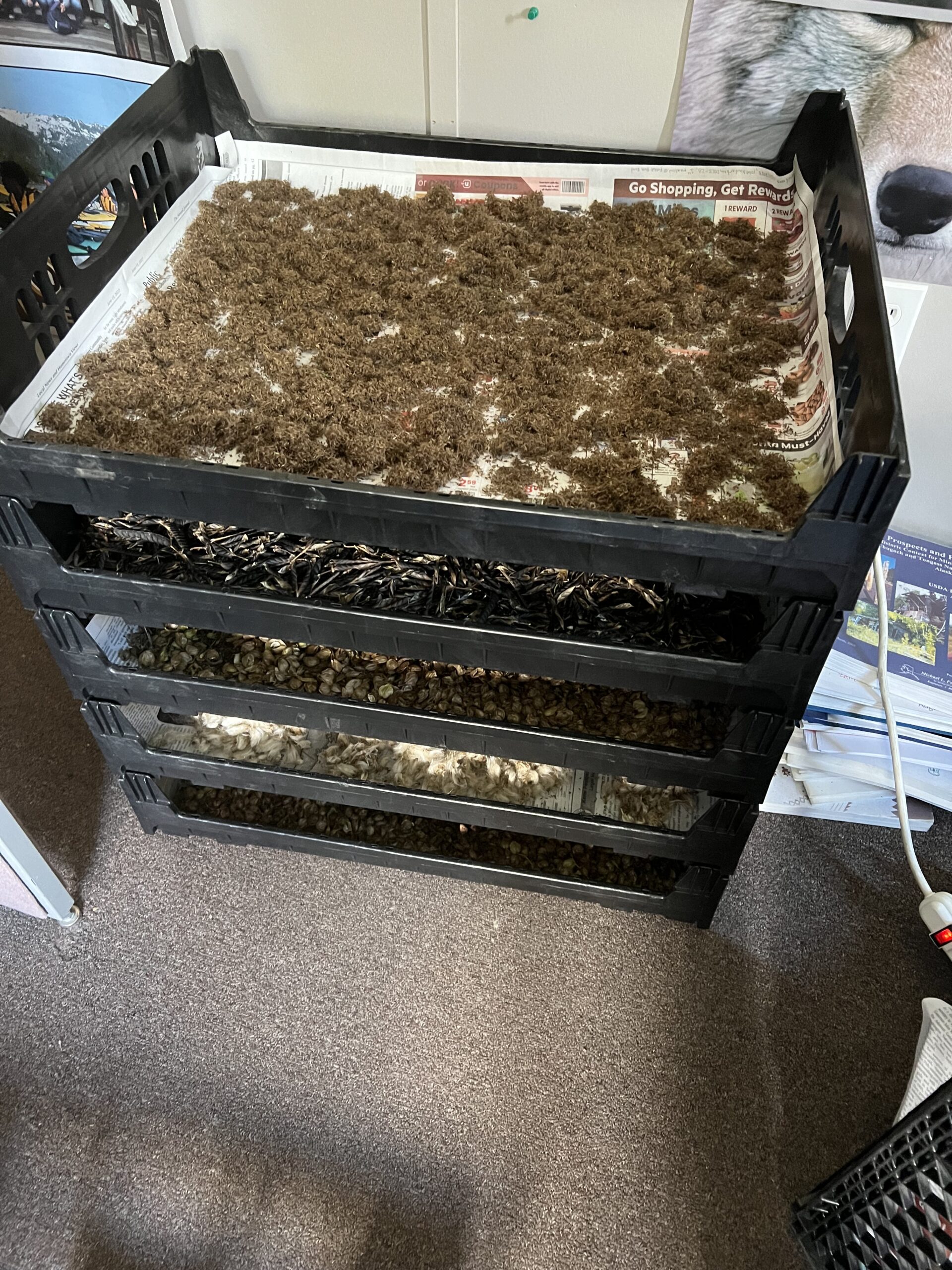

After our final collections, it was time to pack and ship our seed. It was definitely surreal to see a representation of five months of work packed into a stack of boxes. Those boxes don’t even begin to fully represent everything that went into getting that seed. From the long hours spent getting familiar with the plants and the mountain, to the time it took to find suitable populations, to the many miles spent driving and walking, to hours spent sitting at a desk (including the countless interesting conversations and observations that happened along the way), and to the personal growth that’s bound to happen when you spend a summer on the Bighorn mountains.

Now our hard work and growth (both the interns’ and the plants’) is entrusted into the hands of a seed nursery, where the seed will be grown out to produce even more seed so we can have a fall back when the ever-weirding climate continues to threaten our forests and grasslands – a threat I got to see up close and personal this season. The path forward looks to, hopefully, more new friends found in plants and a greater understanding of the world around us. At the end of the day, what more could I ask for?